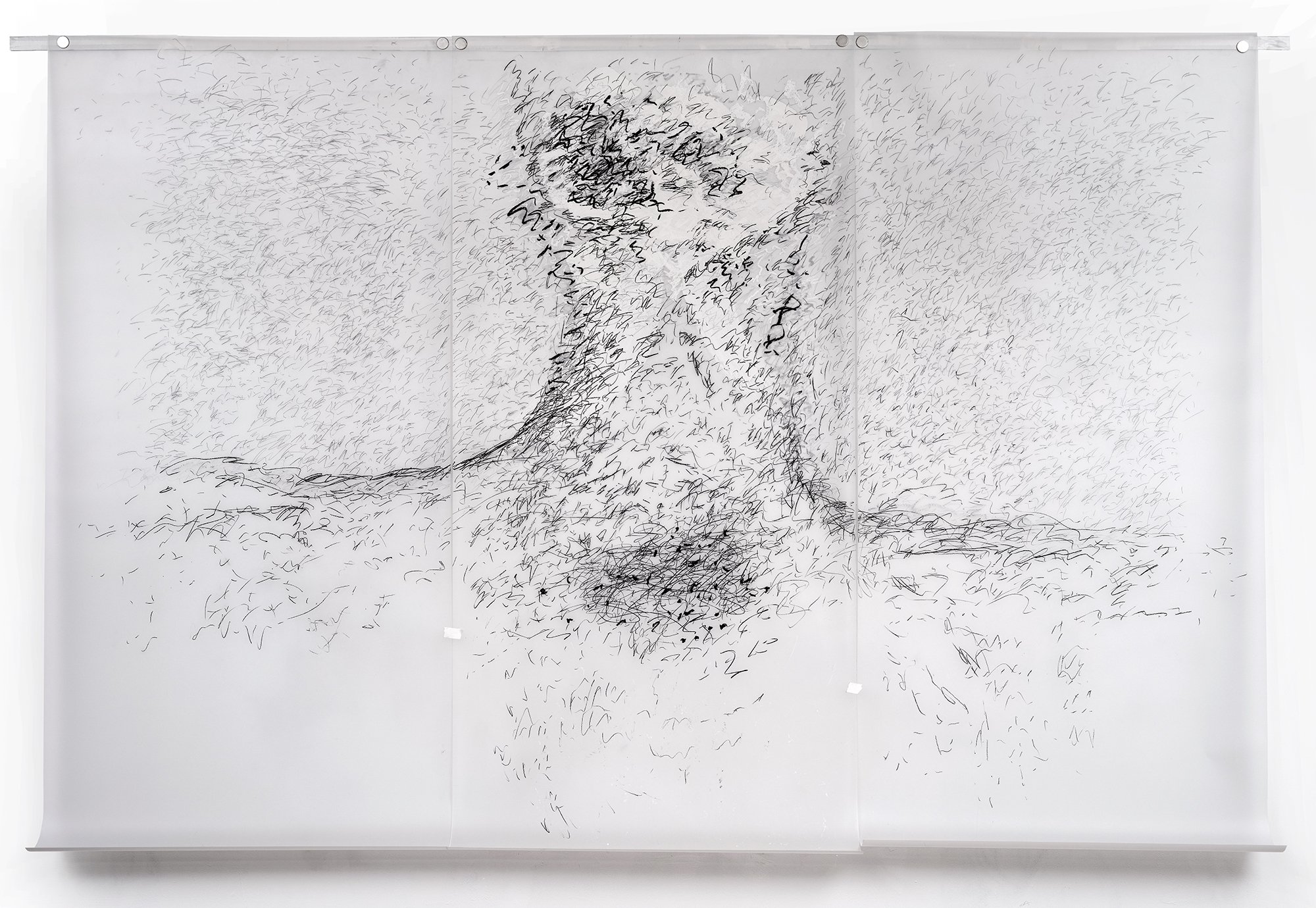

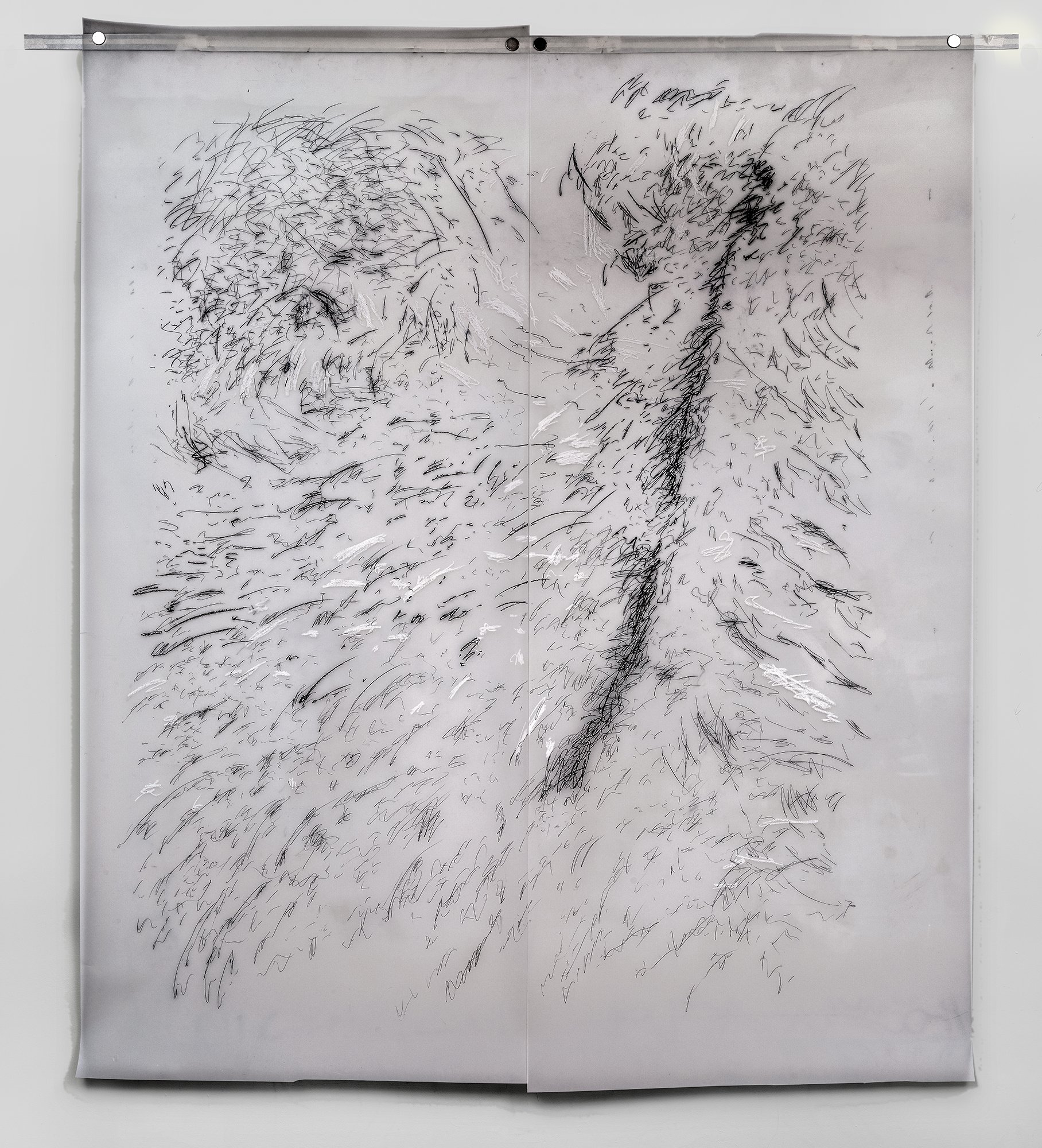

In defiance of the proscenium, I’ve started removing my large drawings from the wall to turn them into mobile, performative “sculptures,” scrims through which to view one another, which implicate the viewer. On wheeled metal structures that telescope in height and which may be choreographed in sequence or side-by-side, the drawings swing free, are shaded by observation, and rattle in the wind currents of the audience. They are drawn on both sides, and are intended to be considered alternate renderings, as internal or external, past and present, creating a form of layered, multi-paneled “diptych.” Their scale and mobility shift the power differentials between maker and viewer, and while these drawings may be read as abstractions, they are in fact depictions of microscopic cytology placed within larger social context, articulating memory in solid form and the objectness of disability.

I've always gravitated toward public spaces to reflect questions of access. Spurred by readjustments to my increasing disabilities, however, the way every social space is simultaneously accessible and restricted is increasingly foregrounded, and I’ve come to think that the way a space is “shared” is a more accurate metric for defining accessibility than “publicness.” What I’m trying to say is our “inner planetarium” is as vast as the spaces around it, and decades of looking outward might've obfuscated deeper inter-relationships between productivity and meaning, memory and history, corporeality and politics. The body, it turns out, is translucent, memory is a solid, agency is gestural, drawing is temporal, social justice is communal.

Our bodies contain a vast, diverse, ever-changing system we are discouraged from exploring or understanding, as if it existed far beyond our reach, like the cosmos. Conversely, the body is the defining subject of colonization, a thing to be explained to us and quantified within highly skewed canons of valuation, the unavoidable core around which all forms of displacement are organized: from gender to gentrification, from forced migration to racial reckoning, from individual identity to political agency.

For some reason, possibly as a means of survival, we are trained to believe the past does not have meaning, only the present and the future do. I think the opposite is true. The present and the future are fantasias based on productivity, and are forms of capital. I believe the only thing with actual form is the past. And memory has so much form it is a solid, and is solid enough to cast a shadow. The future can’t cast its shadow yet. It has to become the past before it does.

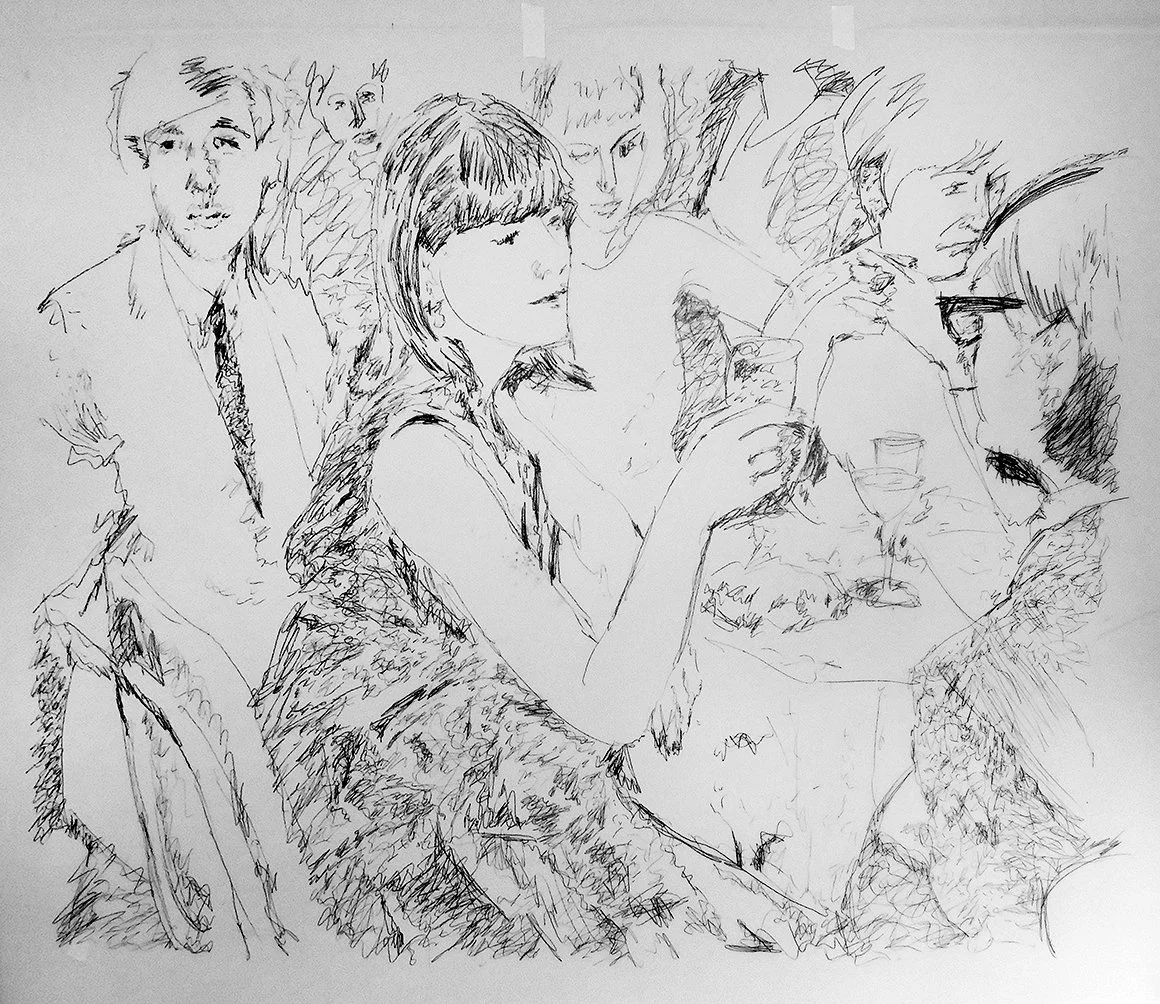

Attempting to come out at the age of 15 led to a psych evaluation at Jewish Family Counseling. It consisted of a thematic apperception test, which was like Rorschach testing, only with drawings that they asked me to describe. The first drawing in this series, reconstructed from memory, is the one I became convinced was the trigger for my court-ordered therapy: when they showed it to me I described it as "something terrible has happened." My brother later scolded me when I recounted it, "you were supposed to say, 'the loving parents are checking in on their children as they sleep.'"

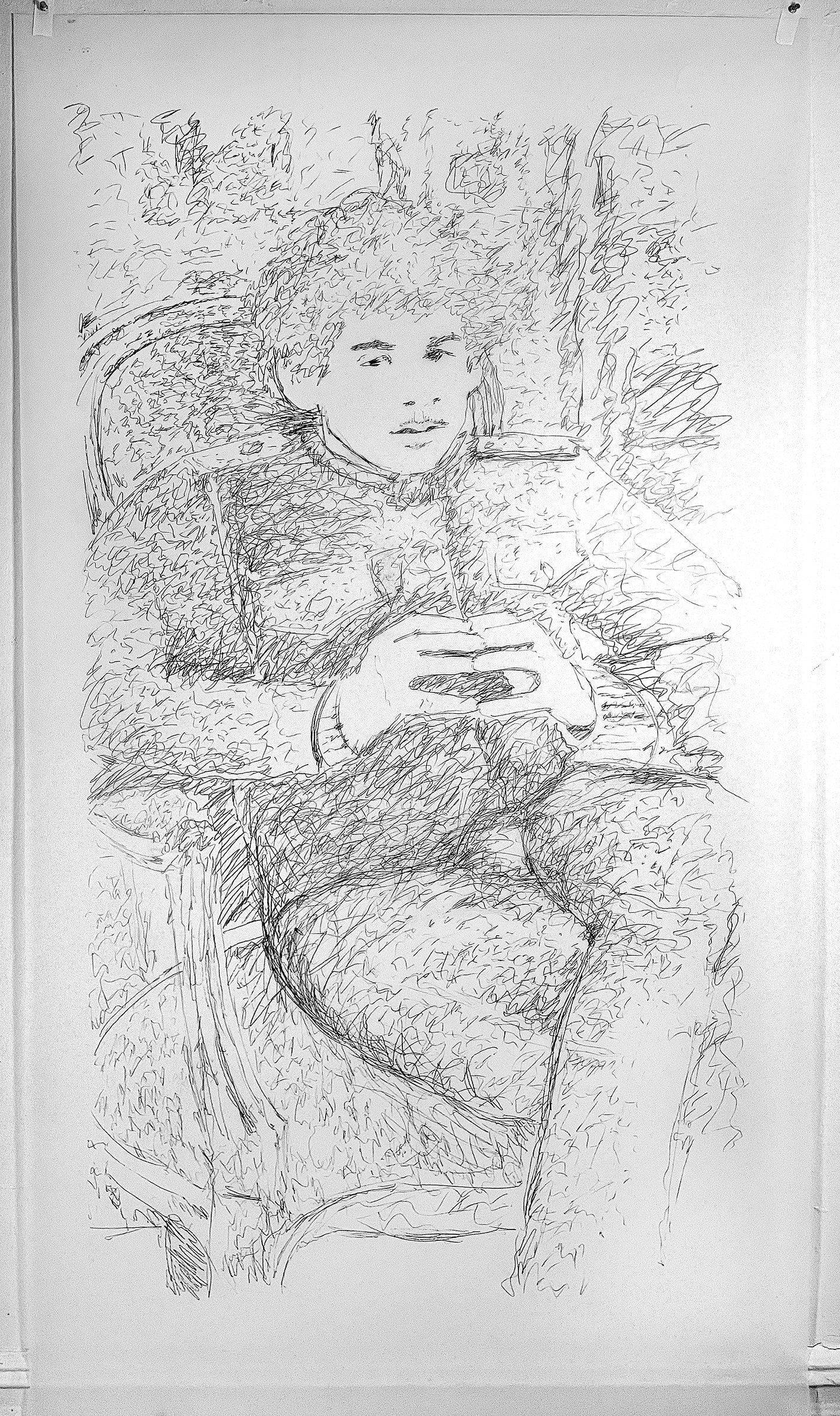

When i was 15, 2 years before the before Stonewall Riots, I attempted to come out. it led to a family meltdown that precipitated a psych evaluation at Jewish Family Counseling in Garden City, after which my brother was committed to Kings Park Psychiatric Hospital and I was sent into Freudian therapy by court order. Paper Dress is named for the silver paper dress my sister wore to a cousin’s wedding. A few months later I went to the first Be-In in NYC, and was photographed by my childhood friend, Joe, the first man I had sex with. A few months after that, he photographed me in Peekskill, looking like I’d aged 10 years. He also took a picture of my brother, under observation at NYU, before he was sent to Kings Park. This suite of drawings is my coming out story.

As I began to lose my sight I realized I didn’t know how much longer I’d be making visual work, and started a suite of drawings to document my family while I still could. My family lived in Red Hook Houses before I was born, then moved to Long Island with financial assistance my father got through the GI Bill. The women on my mother’s side of the family are depicted peeling potatoes in the leftist utopian community we frequented, Goldens Bridge, which is how my father came to work with Ethel Rosenberg. That’s my mother, my sister, my mom’s sister and her mother. All of the women on her side had cancer, and that’s likely how I inherited mine.

This suite of drawings are based on tiny photographs my father took in France during the drawdown of WWII. Even though he was a member of the American Communist Party, he felt compelled to join the army because he was a Jew. His photographs in Le Havre documented no traces of the Holocaust, and even in Paris he used his camera as a shield, the lens serving as a barrier between himself and the world. On the back of the fourth image below he wrote, “You may depict, dimly in the reflection, yours truly.” I believe that phrase defined his relationship with me. He was rarely without a camera, which became a scrim through which he saw the world.

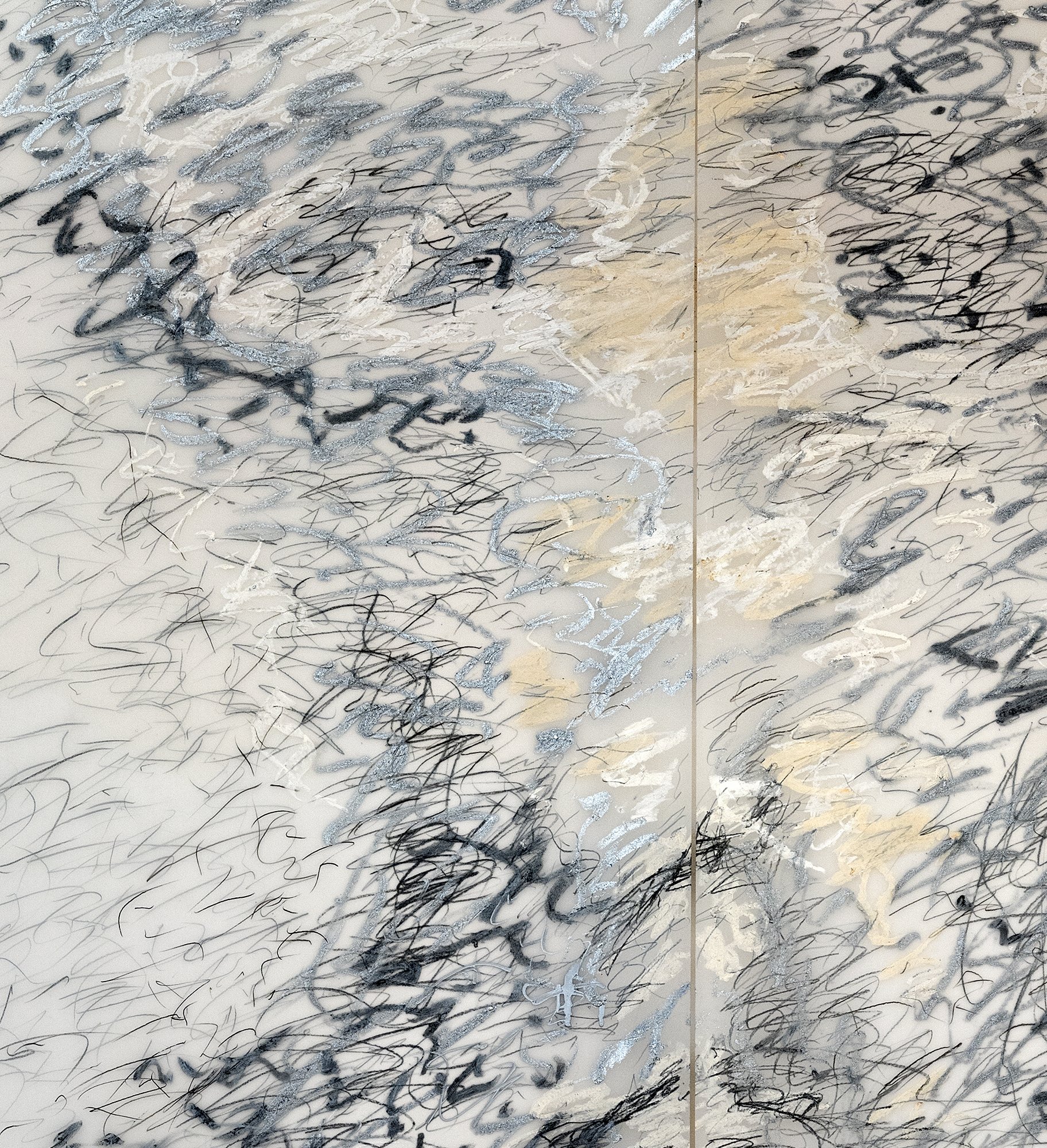

These large gesture drawings document my ongoing accommodations to increasing disability, leading to deeper personal inquiries about corporeality as a system in flux. The drawings are based on enlarged and digitally enhanced note pages from a journal written right after my first loss to AIDS in 1984. The mural-sized re-renderings of my own handwriting led to a series of experiments with text as a simultaneous act of abstraction and documentation, articulated as the distinctions between the parallel acts of memory and witnessing.

The Subway Drawings are a meditation on a single line in Allen Ginsberg’s Howl Footnote, “Holy the mysterious river of tears under the streets.” The graphite drawings are based on iPhone photos of individual tiles in the New York City subway system, each of which are scratched, marked, drawn on and cracked, documentation of centuries of human contact. Together they comprise a vast dossier of the many souls that have brushed against these surfaces, a mysterious river under the streets.

My process is also an elaborate commentary on the passage of time and the meaning of our constantly evolving social spaces: the digital photos are enlarged in tiled sections and printed on eight by ten-inch sheets of newsprint, reassembled with gesso on canvas or craft paper, and then drawn and painted out and redrawn with latex whitewash and graphite. The process of marking and negative mark-making, and the layering of nineteenth and twenty-first century fantasias on egalitarianism – collage-work and digital cell phone technology – comprise an intricate ecosystem of human narratives that touch on the tensions between access and limitation, presence and invisibility, marking and erasure, identity and collectivity.